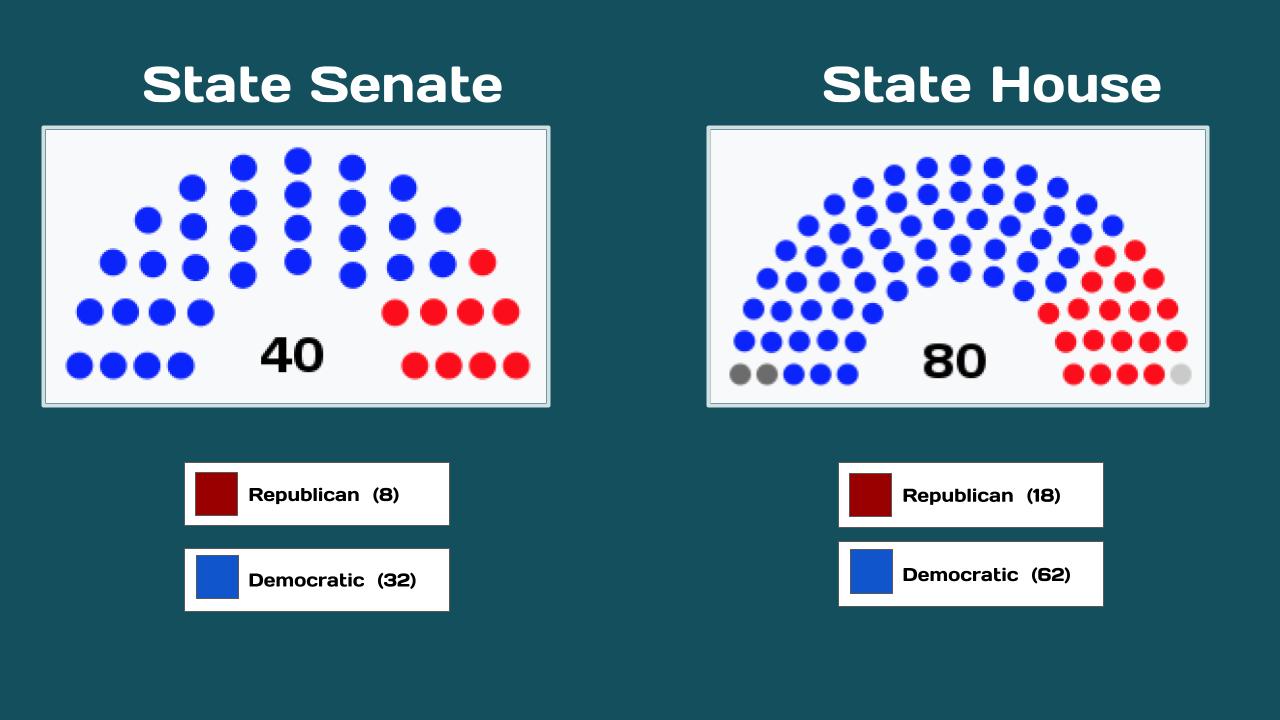

The California State Legislature is a bicameral state legislature consisting of a lower house, the California State Assembly, with 80 members; and an upper house, the California State Senate, with 40 members. Both houses of the Legislature convene at the California State Capitol in Sacramento. The California state legislature is one of just ten full-time state legislatures in the United States.

The Democratic Party currently holds veto-proof supermajorities in both houses of the California State Legislature. The Assembly consists of 60 Democrats and 19 Republicans, with one independent, while the Senate is composed of 30 Democrats and 9 Republicans, also with one vacancy. Except for a brief period from 1995 to 1996, the Assembly has been in Democratic hands since the 1970 election. The Senate has been under continuous Democratic control since 1970.

Source: Wikipedia

OnAir Post: CA Legislature