Summary

Current Position: US Representative of CA District 43 since 1991

Affiliation: Democrat

Former Position: State Delegate from 1976 – 1990

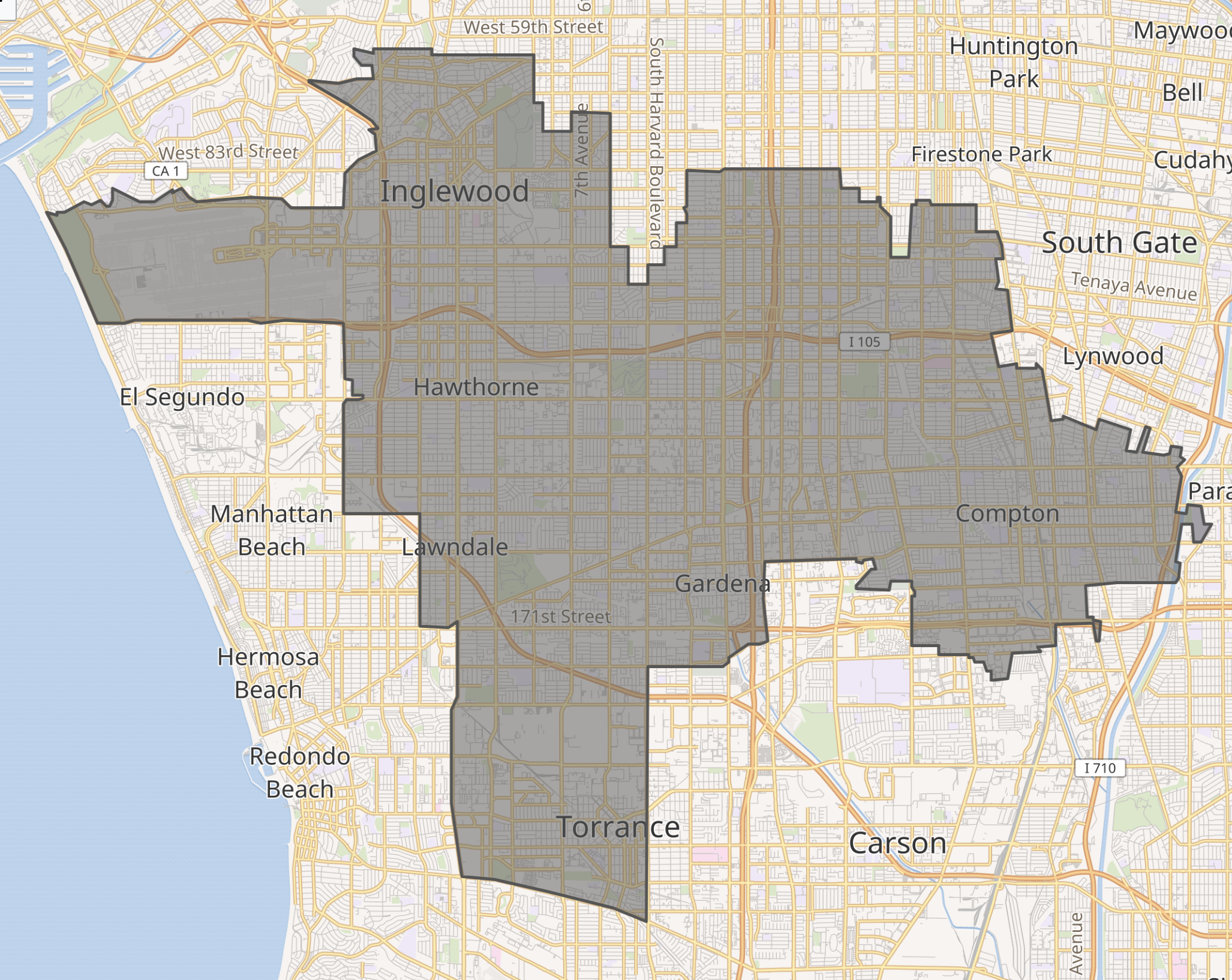

District: southern part of Los Angeles County and includes portions of the cities of Los Angeles (including LAX) and Torrance.

Upcoming Election:

Other positions:

Chair, Committee on Financial Services

Chief Deputy Whip

Quotes:

Today is #NelsonMandelaDay! Had he lived, he would be 103 yrs old. As a legislator in California, I was able to have a bill signed that divested Calif. pension funds from corporations doing business in South Africa. We got Mandela released from prison & ended apartheid!

OnAir Post: Maxine Waters CA-43

News

About

Source: Government page

Elected in November 2018 to her fifteenth term in the U.S. House of Representatives with more than 70 percent of the vote in the 43rd Congressional District of California, Congresswoman Waters represents a large part of South Los Angeles including the communities of Westchester, Playa Del Rey, and Watts and the unincorporated areas of Los Angeles County comprised of Lennox, West Athens, West Carson, Harbor Gateway and El Camino Village. The 43rd District also includes the diverse cities of Gardena, Hawthorne, Inglewood, Lawndale, Lomita and Torrance.

Elected in November 2018 to her fifteenth term in the U.S. House of Representatives with more than 70 percent of the vote in the 43rd Congressional District of California, Congresswoman Waters represents a large part of South Los Angeles including the communities of Westchester, Playa Del Rey, and Watts and the unincorporated areas of Los Angeles County comprised of Lennox, West Athens, West Carson, Harbor Gateway and El Camino Village. The 43rd District also includes the diverse cities of Gardena, Hawthorne, Inglewood, Lawndale, Lomita and Torrance.

Congresswoman Waters made history as the first woman and first African American Chair of the House Financial Services Committee. An integral member of Congressional Democratic Leadership, Congresswoman Waters serves as a member of the Steering & Policy Committee and is the Co-Chair of the bipartisan Congressional Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. She is also a member of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, and member and past chair of the Congressional Black Caucus.

Legislative Leadership

Throughout her more than 40 years of public service, Maxine Waters has been on the cutting edge, tackling difficult and often controversial issues. She has combined her strong legislative and public policy acumen and high visibility in Democratic Party activities with an unusual ability to do grassroots organizing.

Prior to her election to the House of Representatives in 1990, Congresswoman Waters had already attracted national attention for her no-nonsense, no-holds-barred style of politics. During 14 years in the California State Assembly, she rose to the powerful position of Democratic Caucus Chair. She was responsible for some of the boldest legislation California has ever seen: the largest divestment of state pension funds from South Africa; landmark affirmative action legislation; the nation’s first statewide Child Abuse Prevention Training Program; the prohibition of police strip searches for nonviolent misdemeanors; and the introduction of the nation’s first plant closure law.

As a national Democratic Party leader, Congresswoman Waters has long been highly visible in Democratic Party politics and has served on the Democratic National Committee (DNC) since 1980. She was a key leader in five presidential campaigns: Sen. Edward Kennedy (1980), Rev. Jesse Jackson (1984 & 1988), and President Bill Clinton (1992 & 1996). In 2001, she was instrumental in the DNC’s creation of the National Development and Voting Rights Institute and the appointment of Mayor Maynard Jackson as its chair.

Following the Los Angeles civil unrest in 1992, Congresswoman Waters faced the nation’s media and public to interpret the hopelessness and despair in cities across America. Over the years, she has brought many government officials and policy makers to her South Central L.A. district to appeal for more resources. They included President Clinton, Vice President Al Gore, Secretaries of Housing & Urban Development Henry Cisneros and Andrew Cuomo, and Alan Greenspan, chairman of the Federal Reserve System. Following the unrest, she founded Community Build, the city’s grassroots rebuilding project.

She has used her skill to shape public policy and deliver the goods: $10 billion in Section 108 loan guarantees to cities for economic and infrastructure development, housing and small business expansion; $50 million appropriation for “Youth Fair Chance” program which established an intensive job and life skills training program for unskilled, unemployed youth; expanded U.S. debt relief for Africa and other developing nations; creating a “Center for Women Veterans,” among others.

Rep. Waters continues to be an active leader in a broad coalition of residential communities, environmental activists and elected officials that aggressively advocate for the mitigation of harmful impacts of the expansion plan for Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). Furthermore, she continues initiatives to preserve the unique environmental qualities of the Ballona wetlands and bluffs, treasures of her district.

She is a co-founder of Black Women’s Forum, a nonprofit organization of over 1,200 African American women in the Los Angeles area. In the mid-80s, she also founded Project Build, working with young people in Los Angeles housing developments on job training and placement.

As she confronts the issues such as poverty, economic development, equal justice under the law and other issues of concern to people of color, women, children, and poor people, Rep. Waters enjoys a broad cross section of support from diverse communities across the nation.

Throughout her career, Congresswoman Waters has been an advocate for international peace, justice, and human rights. Before her election to Congress, she was a leader in the movement to end Apartheid and establish democracy in South Africa. She opposed the 2004 Haitian coup d’etat, which overthrew the democratically-elected government of Jean-Bertrand Aristide in Haiti, and defends the rights of political prisoners in Haiti’s prisons. She leads congressional efforts to cancel the debts that poor countries in Africa and Latin America owe to wealthy institutions like the World Bank and free poor countries from the burden of international debts.

Congresswoman Waters is the founding member and former Chair of the ‘Out of Iraq’ Congressional Caucus. Formed in June 2005, the ‘Out of Iraq’ Congressional Caucus was established to bring to the Congress an on-going debate about the war in Iraq and the Administration’s justifications for the decision to go to war, to urge the return of US service members to their families as soon as possible.

Expanding access to health care services is another of Congresswoman Waters’ priorities. She spearheaded the development of the Minority AIDS Initiative in 1998 to address the alarming spread of HIV/AIDS among African Americans, Hispanics and other minorities. Under her continuing leadership, funding for the Minority AIDS Initiative has increased from the initial appropriation of $156 million in fiscal year 1999 to approximately $400 million per year today. She is also the author of legislation to expand health services for patients with diabetes, cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

Congresswoman Waters has led congressional efforts to mitigate foreclosures and keep American families in their homes during the housing and economic crises, notably through her role as Chairwoman of the Subcommittee on Housing and Community Opportunity in the previous two Congresses. She authored the Neighborhood Stabilization Program, which provides grants to states, local governments and nonprofits to fight foreclosures, home abandonment and blight and to restore neighborhoods. Through two infusions of funds, the Congresswoman was able to secure $6 billion for the program.

Maxine Waters was born in St. Louis, Missouri, the fifth of 13 children reared by a single mother. She began working at age 13 in factories and segregated restaurants. After moving to Los Angeles, she worked in garment factories and at the telephone company. She attended California State University at Los Angeles, where she earned a Bachelor of Arts degree. She began her career in public service as a teacher and a volunteer coordinator in the Head Start program.

She is married to Sidney Williams, the former U.S. Ambassador to the Commonwealth of the Bahamas. She is the mother of two adult children, Edward and Karen, and has two grandchildren.

Personal

Full Name: Maxine Waters

Gender: Female

Family: Husband: Sidney; 2 Children: Edward, Karen

Birth Date: 08/15/1938

Birth Place: Saint Louis, MO

Home City: Los Angeles, CA

Religion: Christian

Source: Vote Smart

Education

BA, California State University, Los Angeles, 1970

Political Experience

Representative, United States House of Representatives, District 43, 2013-present

Chief Deputy Whip, United States House of Representatives, 1990-present

Candidate, United States House of Representatives, District 43, 2022

Representative, United States House of Representatives, District 35, 1993-2013

Representative, United States House of Representatives, District 29, 1991-1993

Assembly Member, California State Assembly, 1977-1990

Professional Experience

Former Chief Deputy, Office of City Councilor David S. Cunningham

Former Employee, Office of Mayor Tom Bradley

Former Employee, Office of Mervyn M. Dymally

Former Employee, Senator Alan Cranston

Campaign Manager, David S. Cunningham for City Council, 1973

Offices

Washington, DC Office

2221 Rayburn House Office Building

Washington, DC 20515

Phone: (202) 225-2201

Fax: (202) 225-7854

Los Angeles Office

2851 W. 120th Street

Suite H

Hawthorne, CA 90250

Phone: (323) 757-8900

Fax: (323) 757-9506

Contact

Email: Government

Web Links

Politics

Source: none

Election Results

To learn more, go to the wikipedia section in this post.

Finances

Source: Open Secrets

Committees

An integral member of Congressional Democratic Leadership, Congresswoman Waters serves as a member of the Steering & Policy Committee and is the Co-Chair of the bipartisan Congressional Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. She is also a member of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, and member and past chair of the Congressional Black Caucus.

New Legislation

Issues

Source: Government page

More Information

Services

Source: Government page

District

Source: Wikipedia

California’s 43rd congressional district is a congressional district in the U.S. state of California that is currently represented by Democrat Maxine Waters. The district is centered in the southern part of Los Angeles County, and includes portions of the cities of Los Angeles (including LAX) and Torrance. It includes the entirety of the cities of Hawthorne, Lawndale, Gardena, Inglewood, and Lomita. From 2003 until 2013, the 43rd district was based in San Bernardino County. The Hispanic-majority district encompassed the southwestern part of the county, and included San Bernardino and Rialto.

California’s 43rd congressional district is a congressional district in the U.S. state of California that is currently represented by Democrat Maxine Waters. The district is centered in the southern part of Los Angeles County, and includes portions of the cities of Los Angeles (including LAX) and Torrance. It includes the entirety of the cities of Hawthorne, Lawndale, Gardena, Inglewood, and Lomita. From 2003 until 2013, the 43rd district was based in San Bernardino County. The Hispanic-majority district encompassed the southwestern part of the county, and included San Bernardino and Rialto.

Wikipedia

Contents

(Top)

1

Early life and education

2

Early political career

3

U.S. House of Representatives

4

Political positions

5

Personal life

6

Electoral history

7

See also

8

References

9

External links

Maxine Moore Waters (née Carr; born August 15, 1938) is an American politician serving as the U.S. representative for California’s 43rd congressional district since 1991. The district, numbered as the 29th district from 1991 to 1993 and as the 35th district from 1993 to 2013, includes much of southern Los Angeles, as well as portions of Gardena, Inglewood and Torrance.

A member of the Democratic Party, Waters is in her 18th House term. She is the most senior of the 13 black women serving in Congress, and chaired the Congressional Black Caucus from 1997 to 1999.[1] She is the second-most senior member of the California congressional delegation, after Nancy Pelosi. She chaired the House Financial Services Committee from 2019 to 2023 and has been the ranking member since 2023.[2]

Before becoming a U.S. representative, Waters served seven terms in the California State Assembly, to which she was first elected in 1976. As an assemblywoman, she advocated divestment from South Africa‘s apartheid regime. In Congress, she was an outspoken opponent of the Iraq War and has sharply criticized Presidents George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump, whom she has consistently denounced.[3][4]

Waters was included in Time magazine’s list of “100 Most Influential People of 2018.”[5]

Early life and education

Waters was born in 1938 in St. Louis, Missouri, the daughter of Remus Carr and Velma Lee (née Moore).[6][7] The fifth of 13 children, she was raised by her single mother after her father left the family when Maxine was two.[8] She graduated from Vashon High School in St. Louis before moving with her family to Los Angeles in 1961. She worked in a garment factory and as a telephone operator before being hired as an assistant teacher with the Head Start program in Watts in 1966.[8] Waters later enrolled at Los Angeles State College (now California State University, Los Angeles), where she received a bachelor’s degree in sociology in 1971.[9]

Early political career

In 1973, Waters went to work as chief deputy to City Councilman David S. Cunningham Jr. She was elected to the California State Assembly in 1976. In the Assembly, she worked for the divestment of state pension funds from any businesses active in South Africa, a country then operating under the policy of apartheid, and helped pass legislation within the guidelines of the divestment campaign‘s Sullivan Principles.[10] She ascended to the position of Democratic Caucus Chair for the Assembly.[11]

U.S. House of Representatives

Elections

Upon the retirement of Augustus F. Hawkins in 1990, Waters was elected to the United States House of Representatives for California’s 29th congressional district with over 79% of the vote. She has been reelected consistently from this district, renumbered as the 35th district in 1992 and as the 43rd in 2012, with at least 70% of the vote.

Waters has represented large parts of south-central Los Angeles and the Los Angeles coastal communities of Westchester and Playa Del Rey, as well as the cities of Torrance, Gardena, Hawthorne, Inglewood and Lawndale.

Tenure

On July 29, 1994, Waters came to public attention when she repeatedly interrupted a speech by Representative Peter King. The presiding officer, Carrie Meek, classed her behavior as “unruly and turbulent”, and threatened to have the Sergeant at Arms present her with the Mace of the House of Representatives (the equivalent of a formal warning to desist). As of 2017, this is the most recent instance of the mace being employed for a disciplinary purpose. Waters was eventually suspended from the House for the rest of the day. The conflict with King stemmed from the previous day, when they had both been present at a House Banking Committee hearing on the Whitewater controversy. Waters felt King’s questioning of Maggie Williams (Hillary Clinton‘s chief of staff) was too harsh, and they subsequently exchanged hostile words.[12][13][14]

Waters chaired the Congressional Black Caucus from 1997 to 1998. In 2005, she testified at the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce hearings on “Enforcement of Federal Anti-Fraud Laws in For-Profit Education”, highlighting the American College of Medical Technology as a “problem school” in her district.[15] In 2006, she was involved in the debate over King Drew Medical Center. She criticized media coverage of the hospital and asked the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to deny a waiver of the cross ownership ban, and hence license renewal for KTLA-TV, a station the Los Angeles Times owned. She said, “The Los Angeles Times has had an inordinate effect on public opinion and has used it to harm the local community in specific instances.” She requested that the FCC force the paper to either sell its station or risk losing that station’s broadcast rights.[16] According to Broadcasting & Cable, the challenges raised “the specter of costly legal battles to defend station holdings… At a minimum, defending against one would cost tens of thousands of dollars in lawyers’ fees and probably delay license renewal about three months”.[17] Waters’ petition was unsuccessful.[18]

As a Democratic representative in Congress, Waters was a superdelegate to the 2008 Democratic National Convention. She endorsed Democratic U.S. Senator Hillary Clinton for the party’s nomination in late January 2008, granting Clinton nationally recognized support that some suggested would “make big waves.”[19][20][21] Waters later switched her endorsement to U.S. Senator Barack Obama when his lead in the pledged delegate count became insurmountable on the final day of primary voting.[22]

In 2009 Waters had a confrontation with Representative Dave Obey over an earmark in the United States House Committee on Appropriations. The funding request was for a public school employment training center in Los Angeles that was named after her.[23] In 2011, Waters voted against the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012, related to a controversial provision that allows the government and the military to detain American citizens and others indefinitely without trial.[24]

Upon Barney Frank‘s retirement in 2012, Waters became the ranking member of the House Financial Services Committee.[25][26] On July 24, 2013, she voted in favor of Amendment 100 in H.R. 2397 Department of Defense Appropriations Act of 2014.[27] The amendment targeted domestic surveillance activities, specifically that of the National Security Agency, and would have limited the flexibility of the NSA’s interpretation of the law to collect sweeping data on U.S. citizens.[28] Amendment 100 was rejected, 217–205.

On March 27, 2014, Waters introduced a discussion draft of the Housing Opportunities Move the Economy Forward Act of 2014 known as the Home Forward Act of 2014.[29] A key provision of the bill includes the collection of 10 basis points for “every dollar outstanding mortgages collateralizing covered securities”, estimated at $5 billion a year. These funds would be directed to three funds that support affordable housing initiatives, with 75% going to the National Housing trust fund. The National Housing Trust Fund will then provide block grants to states to be used primarily to build, preserve, rehabilitate, and operate rental housing that is affordable to the lowest income households, and groups including seniors, disabled persons and low income workers. The National Housing Trust was enacted in 2008, but has yet to be funded.[30] In 2009, Waters co-sponsored Representative John Conyers‘ bill calling for reparations for slavery to be paid to black Americans.[31]

For her tenure as chair of the House Financial Services Committee in the 116th Congress, Waters earned an “A” grade from the nonpartisan Lugar Center’s Congressional Oversight Hearing Index.[32]

CIA

After a 1996 San Jose Mercury News article alleged the complicity of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the Los Angeles crack epidemic of the 1980s, Waters called for an investigation. She asked whether “U.S.-government paid or organized operatives smuggled, transported and sold it to American citizens”.[33] The United States Department of Justice announced it had failed to find any evidence to support the original story.[34] The Los Angeles Times also concluded after its own extensive investigation that the allegations were not supported by evidence.[35] The author of the original story, Gary Webb, was eventually transferred to a different beat and removed from investigative reporting, before his death in 2004.[36] After these post-publication investigations, Waters read into the Congressional Record a memorandum of understanding in which former President Ronald Reagan‘s CIA director rejected any duty by the CIA to report illegal narcotics trafficking to the Department of Justice.[37][38]

Allegations of corruption

According to Chuck Neubauer and Ted Rohrlich writing in the Los Angeles Times in 2004, Waters’ relatives had made more than $1 million (~$1.59 million in 2024) during the preceding eight years by doing business with companies, candidates and causes that Waters had helped. They claimed she and her husband helped a company get government bond business, and her daughter Karen Waters and son Edward Waters have profited from her connections. Waters replied, “They do their business and I do mine.”[39] Liberal watchdog group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington named Waters to its list of corrupt members of Congress in its 2005, 2006, 2009 and 2011 reports.[40][41] Citizens Against Government Waste named her the June 2009 Porker of the Month due to her intention to obtain an earmark for the Maxine Waters Employment Preparation Center.[42][43]

Waters came under investigation for ethics violations and was accused by a House panel of at least one ethics violation related to her efforts to help OneUnited Bank receive federal aid.[44] Waters’ husband is a stockholder and former director of OneUnited Bank and the bank’s executives were major contributors to her campaigns. In September 2008, Waters arranged meetings between U.S. Treasury Department officials and OneUnited Bank so that the bank could plead for federal cash. It had been heavily invested in Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, and its capital was “all but wiped out” after the U.S. government took it over. The bank received $12 million in Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) money.[45][46] The matter was investigated by the House Ethics Committee,[47][48] which charged Waters with violations of the House’s ethics rules in 2010.[49][50][51][52] On September 21, 2012, the House Ethics Committee completed a report clearing Waters of all ethics charges after nearly three years of investigation.[53]

Objection to 2000 presidential election results

Waters and other House members objected to Florida’s electoral votes, which George W. Bush narrowly won after a contentious recount. Because no senator joined her objection, the objection was dismissed by Vice President Al Gore, who was Bush’s opponent in the 2000 presidential election.[54]

Objection to 2004 presidential election results

Waters was one of 31 House Democrats who voted to not count Ohio’s electoral votes in the 2004 presidential election.[55] President George W. Bush won Ohio by 118,457 votes.[56]

Objection to 2016 presidential election results

Waters objected to Wyoming‘s electoral votes after the 2016 presidential election, a state Donald Trump won with 68.2% of the vote.[57] Because no senator joined her objection, the objection was dismissed by then-Vice President Joe Biden.[58]

“Reclaiming my time”

In July 2017, during a House Financial Services Committee meeting, Waters questioned United States Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin. At several points during the questioning, Waters used the phrase “reclaiming my time” when Mnuchin did not directly address the questions Waters had asked him. The video of the interaction between Waters and Mnuchin became popular on social media, and the phrase became attached to her criticisms of Trump.[59]

Louis Farrakhan

In early 2018, Waters was among the members of Congress the Republican Jewish Coalition called on to resign due to their connections with Nation of Islam leader and known anti-Semite[60] Louis Farrakhan, who had recently drawn criticism for antisemitic remarks.[61][62][63] The Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle noted that Waters had “long embraced Farrakhan” and refused to denounce him, even as other members of the Congressional Black Caucus who secretly met with Farrakhan in 2005 eventually did.[64]

Confrontationalism

Rodney King verdict and Los Angeles riots

When south-central Los Angeles erupted in riots – in which 63 were killed – after the Rodney King verdict in 1992, Waters gained national attention when she led a chant of “No justice, no peace” at a rally amidst the riot.[65] She also “helped deliver relief supplies in Watts and demanded the resumption of vital services”.[66][67] Waters described the riots as a rebellion, saying, “If you call it a riot it sounds like it was just a bunch of crazy people who went out and did bad things for no reason. I maintain it was somewhat understandable, if not acceptable.”[68] In her view, the violence was “a spontaneous reaction to a lot of injustice.” In regard to the looting of Korean-owned stores by local black residents, she said in an interview with KABC radio host Michael Jackson:

There were mothers who took this as an opportunity to take some milk, to take some bread, to take some shoes. Maybe they shouldn’t have done it, but the atmosphere was such that they did it. They are not crooks.[69]

Sarah Huckabee Sanders

On June 23, 2018, after an incident in which White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders was denied service and asked to leave a restaurant, Waters urged attendees at a rally in Los Angeles to harass Trump administration officials, saying:

If you see anybody from [Trump’s] cabinet in a restaurant, in a department store, at a gasoline station, you get out and you create a crowd, and you push back on them, and you tell them they’re not welcome anymore, anywhere.[70][71]

Many on the Right saw this statement as an incitement of violence against officials from the Trump administration.

In response, House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi posted comments on Twitter reported to be a condemnation of Waters’ remarks: “Trump’s daily lack of civility has provoked responses that are predictable but unacceptable.”[72]

Derek Chauvin trial

Comments by Waters on April 17, 2021, while attending protests over the killing of Daunte Wright in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, drew controversy.[73] Responding to questions outside the Brooklyn Center police department[74] – a heavily fortified area that for days had been the site of violent clashes between law enforcement and demonstrators attempting to overrun it[75][76] – Waters commented on the protests and the looming jury verdict in the trial of Derek Chauvin, a former Minneapolis police officer who at the time was charged with murdering George Floyd.[77] Before closing arguments in the trial, Waters said, “I hope we get a verdict that says guilty, guilty, guilty. And if we don’t, we cannot go away”, and when asked, “What happens if we do not get what you just told? What should the people do? What should protesters do?”, Waters responded:

We’ve got to stay on the street. And we’ve got to get more active, we’ve got to get more confrontational, we’ve got to make sure that they know that we mean business.[73][78]

In response to a question from a reporter about the curfew in effect in Brooklyn Center, which loomed shortly,[79] Waters said, “I don’t think anything about curfew … I don’t know what ‘curfew’ means. Curfew means that ‘I want to you all to stop talking, I want you to stop meeting, I want you to stop gathering.’ I don’t agree with that.”[80][81]

The protests outside the Brooklyn Center police station remained peaceful through the night. The crowd grew raucous when the curfew went into effect but shrank shortly after as protesters left on their own and no arrests were reported.[79][82]

The judge in Chauvin’s trial said on April 19, 2021, that Waters’ comments were “abhorrent” and that it was “disrespectful to the rule of law and to the judicial branch” for elected officials to comment in advance of the verdict. The judge refused the defense’s request for a mistrial, saying that the jury “have been told not to watch the news. I trust they are following those instructions”, but also that “Congresswoman Waters may have given you something on appeal that may result in this whole trial being overturned”.[83][84]

After Waters’ comments, Republican minority leader Kevin McCarthy said, “Waters is inciting violence in Minneapolis just as she has incited it in the past. If Speaker Pelosi doesn’t act against this dangerous rhetoric, I will bring action this week”.[81][85][86][87] On April 19, 2021, McCarthy introduced a resolution in the House to censure Waters, calling her comments “dangerous”. The following day, the House voted to block McCarthy’s resolution, narrowly defeating it along party lines, 216–210.[88]

Waters later said that her remarks in Brooklyn Center were taken out of context and that she believed in nonviolent actions. In an interview, she said, “I talk about confronting the justice system, confronting the policing that’s going on, I’m talking about speaking up. I’m talking about legislation. I’m talking about elected officials doing what needs to be done to control their budgets and to pass legislation.”[89]

Bombing attempt

Packages that contained pipe bombs were sent to two of Waters’ offices on October 24, 2018. They were intercepted and investigated by the FBI. No one was injured. Similar packages were sent to several other Democratic leaders and to CNN.[90][91] In 2019, Cesar Sayoc pleaded guilty to mailing the bombs and was sentenced to 20 years in prison.[92][93]

Committee assignments

For the 118th Congress:[94]

- Committee on Financial Services (Ranking Member)

- As Ranking Member of the committee, Rep. Waters is entitled to sit as an ex officio member in any subcommittee meeting, per the committee rules.

Caucus memberships

- Chief Deputy Whip

- Founding member and Chair of the Out of Iraq Caucus

- Congressional Progressive Caucus[95]

- Congressional Black Caucus (CBC); past chair of CBC (105th United States Congress)

- Medicare for All Caucus

- Congressional Caucus for the Equal Rights Amendment[96]

- Congressional Equality Caucus[97]

- United States–China Working Group[98]

- Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus[99]

Political positions

Abortion

Waters has a 100% rating from NARAL Pro-Choice America and an F rating from the Susan B. Anthony List based on her abortion-related voting record.[100][101] She opposed the overturning of Roe v. Wade.[102]

Barack Obama

In August 2011, Waters criticized President Barack Obama, saying he was insufficiently supportive of the black community. She referred to African Americans’ high unemployment rate (around 15.9% at the time).[103] At a Congressional Black Caucus town-hall meeting on jobs in Detroit, Waters said that African American members of Congress were reluctant to criticize or place public pressure on Obama because “y’all love the President”.[104]

In October 2011, Waters had a public dispute with Obama, arguing that he paid more attention to swing voters in the Iowa caucuses than to equal numbers of (geographically dispersed) black voters. In response, Obama said that it was time to “stop complaining, stop grumbling, stop crying” and get back to working with him.[4][105][106]

Crime

Waters opposes mandatory minimum sentences.[107]

Donald Trump

Waters has called Trump “a bully, an egotistical maniac, a liar and someone who did not need to be president”[41] and “the most deplorable person I’ve ever met in my life”.[108] In a 2017 appearance on MSNBC‘s All In with Chris Hayes, she said Trump’s advisors who have ties to Russia or have oil and gas interests there are “a bunch of scumbags”.[109]

Waters began to call for the impeachment of Trump shortly after he took office. In February 2017, she said that Trump was “leading himself” to possible impeachment because of his conflicts of interest and that he was creating “chaos and division”.[110] In September 2017, while giving a eulogy at Dick Gregory‘s funeral, she said that she was “cleaning out the White House” and that “when I get through with Donald Trump, he’s going to wish he had been impeached.”[111] In October 2017, she said the U.S. Congress had enough evidence against Trump to “be moving on impeachment”, in reference to Russian collusion allegations during the 2016 presidential election, and that Trump “has openly obstructed justice in front of our face”.[112]

Linking Trump to the violence that erupted at a white nationalist protest rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, on August 12, 2017, Waters said that the White House “is now the White Supremacists‘ House”.[113][114] After Trump’s 2018 State of the Union address, she released a video response addressing what most members of the Congressional Black Caucus viewed as his racist viewpoint and actions, saying, “He claims that he’s bringing people together but make no mistake, he is a dangerous, unprincipled, divisive, and shameful racist.”[115] Trump later replied by calling her a “low-IQ individual”.[116]

On April 24, 2018, while attending the Time 100 Gala, Waters urged Trump to resign from office, “So that I won’t have to keep up this fight of your having to be impeached because I don’t think you deserve to be there. Just get out.”[117]

On December 18, 2019, Waters voted for both articles of impeachment against Trump.[118] Moments before voting for the second impeachment of Donald Trump, she called him “the worst president in the history of the United States.″[119]

Economy

Cryptocurrency

On June 18, 2019, Waters asked Facebook to halt its plan for the development and launching of Libra, a new cryptocurrency, citing a list of recent scandals. She said: “The cryptocurrency market currently lacks a clear regulatory framework to provide strong protections for investors, consumers and the economy. Regulators should see this as a wake-up call to get serious about the privacy and national security concerns, cybersecurity risks, and trading risks that are posed by cryptocurrencies”.[120]

Foreign affairs

In August 2008, Waters introduced HR 6796, the Stop Very Unscrupulous Loan Transfers from Underprivileged countries from Rich Exploitive Funds Act (Stop VULTURE Funds Act). It would limit the ability of investors in sovereign debt to use U.S. courts to enforce those instruments against a defaulting country. The bill died in committee.[121]

Cuba

Waters has visited Cuba a number of times, praising some of Fidel Castro‘s policy proposals.[122][123][124] She also criticized previous U.S. efforts to overthrow the Castro regime and demanded an end to the U.S. trade embargo.[125] In 1998, Waters wrote Castro a letter calling the 1960s and 1970s “a sad and shameful chapter of our history” and thanking him for helping those who needed to “flee political persecution”.[126]

In 1998, Waters wrote Castro an open letter asking him not to extradite convicted terrorist Assata Shakur from Cuba, where she had sought asylum. Waters argued that much of the Black community regarded her conviction as false.[127][128][129] She had earlier supported a Republican bill to extradite Shakur, who was referred to by her former name, Joanne Chesimard. In 1999, Waters called on President Bill Clinton to return six-year-old Elián González to his father in Cuba; the boy had survived a boat journey from Cuba, during which his mother had drowned, and was taken in by U.S. relatives.[126]

Haiti

Waters opposed the 2004 coup d’état in Haiti and criticized U.S. involvement.[130] After the coup, she, TransAfrica Forum founder Randall Robinson, and Jamaican member of parliament Sharon Hay-Webster led a delegation to meet with Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide and bring him to Jamaica, where he remained until May.[131][132][133]

Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

On October 1, 2020, Waters co-signed a letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo that condemned Azerbaijan‘s offensive operations against the Armenian-populated enclave Nagorno-Karabakh, denounced Turkey‘s role in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and called for an immediate ceasefire.[134]

George H. W. Bush

In July 1992, Waters called President George H. W. Bush “a racist” who “polarized the races in this country”. Previously, she had suggested that Bush had used race to advance his policies.[135]

Tea Party movement

Waters has been very critical of the Tea Party movement. On August 20, 2011, at a town hall discussing some of the displeasure that Obama’s supporters felt about the Congressional Black Caucus not supporting him, Waters said, “This is a tough game. You can’t be intimidated. You can’t be frightened. And as far as I’m concerned, the ‘tea party’ can go straight to Hell … and I intend to help them get there.”[136][137]

War

Iraq War

Waters voted against the Iraq War Resolution, the 2002 resolution that funded and granted Congressional approval to possible military action against the regime of Saddam Hussein.[138] She has remained a consistent critic of the subsequent war and has supported immediate troop withdrawal from Iraq. Waters asserted in 2007 that President George W. Bush was trying to “set [Congress] up” by continually requesting funds for an “occupation” that was “draining” the country of capital, soldier’s lives, and other resources. In particular, she argued that the economic resources being “wasted” in Iraq were those that might provide universal health care or fully fund Bush’s “No Child Left Behind” education bill. Additionally, Waters, representing a congressional district whose median income falls far below the national average, argued that patriotism alone had not been the sole driving force for those U.S. service personnel serving in Iraq. Rather, “many of them needed jobs, they needed resources, they needed money, so they’re there”.[139] In a subsequent floor speech, she said that Congress, lacking the votes to override the “inevitable Bush veto on any Iraq-related legislation,” needed to “better [challenge] the administration’s false rhetoric about the Iraq war” and “educate our constituents [about] the connection between the problems in Pakistan, Turkey, and Iran with the problems we have created in Iraq”.[140] A few months before these speeches, Waters cosponsored the House resolution to impeach Vice President Dick Cheney for making allegedly “false statements” about the war.[141]

Personal life

Waters’ second husband, Sid Williams, played professional football in the NFL[142] and is a former U.S. ambassador to the Bahamas under the Clinton administration.[143] They live in Los Angeles’ Windsor Square neighborhood.[144]

In May 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Waters confirmed her sister, Velma Moody, had died of the virus, aged 86.[145]

Other achievements

- Maxine Waters Preparation Center in Watts, California – named after her while she was a member of the California Assembly

- Co-founder of Black Women’s Forum

- Co-founder of Community Build

- Received the Bruce F. Vento Award from the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty for her work on behalf of homeless persons.

- Candace Award, National Coalition of 100 Black Women, 1992[146]

- Received the 2025 PFLAG National Champion of Justice award[147]

Electoral history

California State Assembly

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Maxine Waters | 38,133 | 80.6 | |

| Republican | Johnnie G. Neely | 9,188 | 19.4 | |

| Total votes | 47,321 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 30,449 | 80.8 | |

| Republican | Timothy F. Faulkner | 7,247 | 19.2 | |

| Total votes | 37,696 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 39,660 | 82.9 | |

| Republican | Yva Hallburn | 8,194 | 17.1 | |

| Total votes | 47,854 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 54,209 | 100 | |

| Total votes | 54,209 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 59,507 | 85.8 | |

| Republican | Donald “Don” Weiss | 9,884 | 14.2 | |

| Total votes | 69,391 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 42,706 | 84.5 | |

| Republican | Ezola Foster | 6,450 | 12.8 | |

| Libertarian | José “Joe” Castañeda | 1,360 | 2.7 | |

| Total votes | 50,516 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 49,946 | 100 | |

| Total votes | 49,946 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

U.S. House of Representatives

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters | 36,182 | 88.5 | |

| Democratic | Lionel Allen | 2,666 | 6.5 | |

| Democratic | Twain Wilson | 1,115 | 2.7 | |

| Democratic | Ted Andromidas | 930 | 2.3 | |

| Total votes | 40,893 | 100 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters | 51,350 | 79.4 | |

| Republican | Bill DeWitt | 12,054 | 18.6 | |

| Peace and Freedom | Waheed R. Boctor | 1,268 | 2.0 | |

| Total votes | 64,672 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 51,534 | 89.2 | |

| Democratic | Roger A. Young | 6,252 | 10.8 | |

| Total votes | 57,786 | 100 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 102,941 | 82.5 | |

| Republican | Nate Truman | 17,417 | 14.0 | |

| Peace and Freedom | Alice Mae Miles | 2,797 | 2.2 | |

| Libertarian | Carin Rogers | 1,618 | 1.3 | |

| Total votes | 124,773 | 100 | ||

| Democratic gain from Republican | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 65,688 | 78.1 | |

| Republican | Nate Truman | 18,390 | 21.9 | |

| American Independent | Gordan Mego (write-in) | 3 | nil | |

| Total votes | 84,081 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 92,762 | 85.5 | |

| Republican | Eric Carlson | 13,116 | 12.1 | |

| American Independent | Gordan Mego | 2,610 | 2.4 | |

| Total votes | 108,398 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 78,732 | 89.3 | |

| American Independent | Gordan Mego | 9,413 | 10.7 | |

| Total votes | 88,145 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 100,569 | 86.5 | |

| Republican | Carl McGill | 12,582 | 10.8 | |

| American Independent | Gordan Mego | 1,911 | 1.6 | |

| Natural Law | Rick Dunstan | 1,153 | 1.0 | |

| Total votes | 116,215 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 72,401 | 77.5 | |

| Republican | Ross Moen | 18,094 | 19.4 | |

| American Independent | Gordan Mego | 2,912 | 3.1 | |

| Total votes | 93,407 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 125,949 | 80.5 | |

| Republican | Ross Moen | 23,591 | 15.1 | |

| American Independent | Gordan Mego | 3,440 | 2.2 | |

| Libertarian | Charles Tate | 3,427 | 2.2 | |

| Total votes | 156,407 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 31,010 | 86.1 | |

| Democratic | Carl McGill | 5,000 | 13.9 | |

| Total votes | 36,010 | 100 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 82,498 | 83.8 | |

| American Independent | Gordan Mego | 8,343 | 8.5 | |

| Libertarian | Paul Ireland | 7,665 | 7.8 | |

| Total votes | 98,506 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 36,685 | 100 | |

| Total votes | 36,685 | 100 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 150,778 | 82.6 | |

| Republican | Theodore Hayes Jr. | 24,169 | 13.2 | |

| Libertarian | Herbert G. Peters | 7,632 | 4.2 | |

| Total votes | 182,579 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 32,946 | 100 | |

| Total votes | 32,946 | 100 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 98,131 | 79.3 | |

| Republican | K. Bruce Brown | 25,561 | 20.7 | |

| Independent | Suleiman Charles Edmondson (write-in) | 2 | nil | |

| Total votes | 123,694 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 36,062 | 65.4 | |

| Democratic | Bob Flores | 19,061 | 34.5 | |

| Total votes | 55,123 | 100 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 143,123 | 71.2 | |

| Democratic | Bob Flores | 57,771 | 28.8 | |

| Total votes | 200,894 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 33,746 | 67.2 | |

| Republican | John Wood Jr. | 16,440 | 32.8 | |

| American Independent | Brandon M. Cook (write-in) | 12 | nil | |

| Total votes | 50,198 | 100 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 69,681 | 71.0 | |

| Republican | John Wood Jr. | 28,521 | 29.0 | |

| Total votes | 99,202 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 92,909 | 76.1 | |

| Republican | Omar Navarro | 29,152 | 23.9 | |

| Total votes | 122,061 | 100 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 167,017 | 76.1 | |

| Republican | Omar Navarro | 52,499 | 23.9 | |

| Total votes | 219,516 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 63,908 | 72.4 | |

| Republican | Omar Navarro | 12,522 | 14.1 | |

| Republican | Frank T. DeMartini | 6,156 | 7.0 | |

| Republican | Edwin P. Duterte | 3,673 | 4.3 | |

| Green | Miguel Angel Zuniga | 2,074 | 2.4 | |

| Total votes | 88,333 | 100 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 152,272 | 77.7 | |

| Republican | Omar Navarro | 43,780 | 22.3 | |

| Total votes | 196,052 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 100,468 | 78.1 | |

| Republican | Joe Edward Collins III | 14,189 | 11.0 | |

| Republican | Omar Navarro | 13,939 | 10.8 | |

| Total votes | 128,596 | 100 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 199,210 | 71.7 | |

| Republican | Joe Edward Collins III | 78,688 | 28.3 | |

| Total votes | 277,898 | 100 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 55,889 | 74.3 | |

| Republican | Omar Navarro | 8,927 | 11.9 | |

| Republican | Allison Pratt | 5,489 | 7.3 | |

| Democratic | Jean Monestime | 4,952 | 6.6 | |

| Total votes | 75,257 | 100.0 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 95,462 | 77.3 | |

| Republican | Omar Navarro | 27,985 | 22.7 | |

| Total votes | 123,447 | 100.0 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 54,673 | 69.8 | |

| Republican | Steve Williams | 10,896 | 13.9 | |

| Republican | David Knight | 5,647 | 7.2 | |

| Democratic | Chris Wiggins | 4,999 | 6.4 | |

| Democratic | Gregory Cheadle | 2,075 | 2.7 | |

| Total votes | 78,290 | 100.0 | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Maxine Waters (incumbent) | 160,080 | 75.1 | |

| Republican | Steve Williams | 53,152 | 24.9 | |

| Total votes | 213,232 | 100.0 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

See also

- List of African-American United States representatives

- Women in the United States House of Representatives

References

- ^ “Membership”. Congressional Black Caucus. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ Neukam, Stephen (January 10, 2023). “New Congress: Here’s who’s heading the various House Committees”. The Hill. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ Gstalter, Morgan (May 29, 2019). “Maxine Waters: Trump should resign and ‘free us’ from impeachment proceedings”. The Hill. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ a b Williams, Joseph Williams (October 20, 2011), ” Obama learns perils of roiling Waters”, Politico, October 20, 2011.

- ^ “Maxine Waters: The World’s 100 Most Influential People”. Time. Archived from the original on June 14, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ “Next up for House Ethics trial: St. Louis native Maxine Waters”. stltoday. November 19, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ “Waters, Maxine”. Contemporary Black Biography. Encyclopedia.com. 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ a b Brownstein, Ronald (March 5, 1989). “The Two Worlds of Maxine Waters”. Los Angeles Times Magazine. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ “Public Affairs Office – Who’s Who of Cal State L.A. Alumni”. Cal State LA. October 22, 2013.

- ^ French, Howard W. (February 9, 1987). “Slash Ties, Apartheid Foes Urge”. The New York Times. p. D1. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

Maxine Waters, a member of the California Assembly who helped frame her state’s pension fund divestment bill, has promised to work overtime to insure that our legislation reflects these guidelines and continues to target any and all U.S. companies that are doing business in or with South Africa.

- ^ “About Congresswoman Maxine Waters: Representing the 35th District of California”. Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

During 14 years in the California State Assembly, she rose to the powerful position of Democratic Caucus Chair. She was responsible for some of the boldest legislation California has ever seen: the largest divestment of state pension funds from South Africa; landmark affirmative action legislation; the nation’s first statewide Child Abuse Prevention Training Program; the prohibition of police strip searches for nonviolent misdemeanors; and the introduction of the nation’s first plant closure law.

- ^ Manegold, Catherine S. (July 30, 1994). “Sometimes the Order of the Day Is Just Maintaining Order”. The New York Times. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Hawthorne, California; C-SPAN [1] What is the staff with an eagle on top they keep moving around in the House? What is it used for? March 5, 2000 Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Whitewater Controversy House Floor, Jul 29 1994 | Video | C-SPAN.org”. www.c-span.org. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ “Testimony of the Honorable Maxine Waters”. House. Archived from the original on December 13, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Waters, Maxine (November 1, 2006). “Petition to Deny Request for Renewal of Broadcast License”. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

Tribune influenced public opinion in the Los Angeles DMA to harm its residents and one of its most critical public health facilities – the Martin Luther King/Drew Medical Center (King/Drew).

- ^ McConnell, Bill (September 19, 2004). “Your Money or Your License”. Broadcasting & Cable. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ^ “Station Search Details”. Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

Call Sign: KTLA… Channel: 5… Lic Expir: 12/01/2014

- ^ “The endorsements that would make huge waves”. The Hill. December 6, 2007. Archived from the original on December 8, 2007. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.). The outspoken anti-war liberal, who campaigned for Ned Lamont (D) over U.S. Senator Joe Lieberman (I) from Connecticut last year, has not picked a favorite.

- ^ Bombardieri, Marcella (January 29, 2008). “Maxine Waters for Clinton – 2008 Presidential Campaign Blog – Political Intelligence”. The Boston Globe. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ Bombardieri, Marcella (January 29, 2008). “Maxine Waters for Clinton”. The Boston Globe.

- ^ Bosman, Julie (June 3, 2008). “The Superdelegate Tally”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Allen, Jared; Soraghan, Mike (June 25, 2009). “Obey, Waters in noisy floor fight”. The Hill. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

- ^ Sheets, Connor (December 16, 2011). “NDAA Bill: How Did Your Congress Member Vote?”. International Business Times.

- ^ Becker, Bernie; Schroeder, Peter (November 28, 2011). “Maxine Waters in line to take over from Frank on Financial Services Committee”. The Hill. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- ^ Crittenden, Michael R (December 4, 2012). “Maxine Waters to Succeed Barney Frank on Banking Panel”. WSJ Blog Washington Wire. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ “Final Vote Results For Roll Call 412”. US House of Representatives.

- ^ “Why The NSA and President Bush Got The FISA Court to Reinterpret The Law in Order To Collect Tons Of Data”. Tech Dirt. June 17, 2013.

- ^ Siegel, Robert M.; Sahn, Jeremy C (April 9, 2014). “Recently Unveiled “Home Forward” Housing Act May Signal the End of Fannie and Freddie”. The National Law Review. Bilzin Sumberg Baena Price & Axelrod LLP. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ “H.R Bill – 113th Congress 2D Session [Discussion Draft] ‘Housing Opportunities Move the Economy Forward Act 5 of 2014’ or the ‘Home Forward Act of 2014’“ (PDF). Government Printing Office. 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ “H.R. 40 (111th): Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act”. GovTrack.

- ^ “Congressional Oversight Hearing Index”. Welcome to the Congressional Oversight Hearing Index. The Lugar Center. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Waters, Maxine (August 30, 1996). “Drugs”. The Narco News Bulletin. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

What those articles traced, among other things, is the long-term relationship between Norwin Meneses, a Nicaraguan drug trafficker, Danilo Blandon, a Nicaraguan businessperson connected to the Contra rebels as well as a drug trader, and Ricky Ross, an American who worked with Blandon distributing crack cocaine in this country. These individuals represent a much broader and more troubling relationship between U.S. intelligence and security policy, drug smuggling, and the spread of crack cocaine into the United States. Letter to U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno

- ^ Cockburn, Alexander; Jeffrey St Clair (1999). Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-258-5.

- ^ “CIA-Contra-Crack Cocaine Controversy”.

- ^ Osborn, Barbara Bliss (March 1, 1998). “‘Are You Sure You Want to Ruin Your Career?’ Gary Webb’s fate a warning to gutsy reporters”. Fair.

- ^ Waters, Maxine (May 7, 1998). “Casey”. Congressional Record?. California State University Northridge. pp. H2970–H2978. Archived from the original on September 10, 2004. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ “Casey”. Archived from the original on September 10, 2004. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ Chuck Neubauer and Ted Rohrlich Capitalizing on a Politician’s Clout; The husband, daughter and son of Rep. Maxine Waters have business links to people the influential lawmaker has aided Archived September 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine; The Los Angeles Times. December 19, 2004. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- ^ “Maxine Waters”. CREW’s Most Corrupt. Archived from the original on May 18, 2012.

- ^ a b Yamiche Alcindor, ‘Auntie Maxine’ Waters Goes After Trump and Goes Viral, New York Times (July 7, 2017).

- ^ “Rep. Maxine Waters is CAGW’s June Porker of the Month”. Citizens Against Government Waste. April 2009. Archived from the original on June 23, 2009. Retrieved July 11, 2009.

- ^ Wood, Daniel B. (August 3, 2010), “Maxine Waters: charges highlight mixed ethics record”, The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ Simon, Richard; Mascaro, Lisa (July 31, 2010). “Maxine Waters faces ethics charges”. Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Schmidt, Susan (March 12, 2009). “Waters Helped Bank Whose Stock She Once Owned”. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

Ms. Waters, who represents inner-city Los Angeles, hasn’t made a secret of her family’s financial interest in OneUnited. Referring to her family’s investment, she said in 2007 during a congressional hearing that for African-Americans, “the test of your commitment to economic expansion and development and support for business is whether or not you put your money where your mouth is.”

- ^ Lipton, Eric; Rutenberg, Jim; Walsh, Barclay (March 12, 2009). “Congresswoman, Tied to Bank, Helped Seek Funds”. The New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

Top federal regulators say they were taken aback when they learned that a California congresswoman who helped set up a meeting with bankers last year had family financial ties to a bank whose chief executive asked them for up to $50 million in special bailout funds.

- ^ Margasak, Larry (September 16, 2009). “Ethics panel defers probe on Jesse Jackson Jr”. Associated Press. Retrieved September 16, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Simon, Richard (August 6, 2012). “Maxine Waters: House ethics panel extends case of L.A. lawmaker”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Lipton, Eric (July 31, 2010). “Ethics Inquiry on Waters Is Tied to OneUnited Bank”. The New York Times.

- ^ Bacon, Perry Jr. (August 13, 2010). “Maxine Waters defends herself publicly on ethics charges”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012.

- ^ Lewis, Tara A. (August 9, 2010). “Rep. Maxine Waters Faces Three Charges”. Newsweek.

- ^ Lipton, Eric (July 30, 2010). “Ethics Trial Expected for California Congresswoman”. The New York Times.

- ^ Hederman, Rosaline (September 21, 2012). “Maxine Waters cleared of House ethics charges”. The Washington Post. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ “Objections Aside, a Smiling Gore Certifies Bush”. Los Angeles Times. January 7, 2001.

- ^ “Final Vote Results for Role Call 7”. Clerk of the United States House of Representatives. January 6, 2005. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Salvato, Albert (December 29, 2004). “Ohio Recount Gives a Smaller Margin to Bush”. The New York Times.

- ^ “2016 Presidential Election Results – The New York Times”. The New York Times. August 9, 2017. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- ^ Williams, Brenna (January 6, 2017). “11 times VP Biden was interrupted during Trump’s electoral vote certification”. CNN Politics.

- ^ Romano, Ajo (July 31, 2017). “Reclaiming my time: Maxine Waters’ beleaguered congressional hearing led to a mighty meme”. Vox. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ *“Louis Farrakhan”. Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- “The Nation of Islam “Louis Farrakhan: America’s Leading Anti-Semite”“. Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- Kass, John (March 6, 2018). “Louis Farrakhan’s anti-Semitism and the silence of the left”. chicagotribune.com. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- Stern, Marlow (June 17, 2020). “Hollywood Celebs Are Praising an Anti-Semitic Hatemonger”. The Daily Beast. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- “Fox Soul Announces It Will Not Broadcast Louis Farrakhan July 4 Address”. Jewish Journal. June 29, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- “Revisiting Louis Farrakhan’s Influence Amid Celebrities’ Anti-Semitic Comments”. NPR.org. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- Burke, Daniel (May 9, 2019). “A Catholic church hosted Louis Farrakhan for an anti-Facebook speech. At least one Jewish group was not happy about it”. CNN. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- “Republican Jewish Coalition calls for resignation of 7 Democrats over ‘ties’ to Farrakhan”. ABC News. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- Cohen, Richard. “Opinion | Why does the left still associate with Louis Farrakhan?”. The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ “Republican Jewish Coalition calls for resignation of 7 Democrats over ‘ties’ to Farrakhan”. ABC News. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Manchester, Julia (March 6, 2018). “Jewish GOP group calls on Dem lawmakers to resign over Farrakhan remarks”. The Hill. Capitol Hill Publishing. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ Lima, Cristiano (March 8, 2018). “Dems denounce Farrakhan rhetoric amid pressure from GOP”. Politico. Capitol News Company. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ Dunst, Charles. “Should Clinton have shared a stage with Farrakhan at Aretha Franklin’s funeral?”. Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ Newman, Maria (May 19, 1992), “After the Riots: Washington at Work; Lawmaker From Riot Zone Insists On a New Role for Black Politicians”, The New York Times.

- ^ Louise Donahue Rep. Maxine Waters to speak at annual MLK Convocation on February 20 January 15, 2007 Currents (UC Santa Cruz)

- ^ “Maxine Water”. PBS.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Pandey, Swati (April 29, 2007). “Was it a ‘riot,’ a ‘disturbance’ or a ‘rebellion’?”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Shuit, Douglas P. (May 10, 1992). “Waters Focuses Her Rage at System”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ Ehrlich, Jamie (June 25, 2018). “Democratic congresswoman encourages supporters to harass Trump administration officials”. CNN. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ Calfas, Jennifer (June 25, 2018). “‘They’re Not Welcome Anymore, Anywhere.’ Maxine Waters Tells Supporters to Confront Trump Officials”. Time. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Pramuk, Jacob (June 25, 2018). “Pelosi rebukes Democratic Rep. Maxine Waters for urging supporters to confront Trump administration officials”. CNBC. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Edmondson, Catie (April 19, 2021). “A defense lawyer and the judge suggest a congresswoman’s comments could offer grounds for appeal”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Desmond, Declan (April 18, 2021). “Maxine Waters speaks in Brooklyn Center, draws ire of right-wing media”. Bring Me the News. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Kieth, Theo (April 16, 2021). “Walz: Tear gas in Brooklyn Center meant to avoid another police station burning”. FOX-9. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Liz Navratil, Ryan Faircloth, Liz Navratil and Ryan Faircloth, Navratil, Liz; Faircloth, Ryan; Faircloth, Ryan (April 17, 2021). “As curfew passes, Brooklyn Center protest remains peaceful”. Star Tribune. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee, Kurtis; Hennessy-Fiske, Molly (April 19, 2021). “Derek Chauvin’s fate in the death of George Floyd is now in the hands of the jury”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Cillizza, Chris (April 19, 2021). “Maxine Waters just inflamed a very volatile situation”. The Po!nt with Chris Cillizza. CNN. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Cashman, Tyler; Korynta, Emma Korynta (April 17, 2021). “Demonstrations continue for seventh straight night outside Brooklyn Center police department”. KARE-11. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Waters, Maxine (April 19, 2021). “Congresswoman Maxine Waters Urges Daunte Wright Protesters to Continue”. Unicorn Riot (Interview). Brooklyn Center, Minnesota. 6 minutes 18 seconds in. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2021 – via YouTube. Question: “…George Floyd is waking so many people up, yet nothing’s happened despite the rhetoric. What needs to happen that’s different this year than all the years before?” Waters: “We’re looking for a guilty verdict … and we’re looking to see if all the talk that took place and has been taking place after they talk, what happened to George Floyd, if nothing does not happen, [sic] then we know that we’ve got to not only stay in the street, but we’ve got to fight for justice. But I am very hopeful, and I hope, that we’re going to get a verdict that does say guilty, guilty, guilty, and if we don’t, we cannot go away.” … Q: “What happens if we do not get what you just told? What should the people do? What should protestors do?” Waters: “I didn’t hear you.” Q: “What should protestors do?” Waters: “Well, we gotta stay on the street. And we’ve got to get more active, we’ve got to get more confrontational, we’ve got to make sure that they know that we mean business.” Q: “What do you think about this curfew tonight?” Waters: “I don’t think anything about curfew; I don’t think any about curfew. I don’t know what ‘curfew’ means. Curfew means that ‘I want to you all to stop talking, I want you to stop meeting, I want you to stop gathering.’ I don’t agree with that.”

- ^ a b Duster, Chandelis (April 19, 2021). “Waters calls for protesters to ‘get more confrontational’ if no guilty verdict is reached in Derek Chauvin trial”. CNN. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Navratil, Liz; Faircloth, Ryan; Navratil, Liz; Faircloth, Ryan (April 17, 2021). “As curfew passes, Brooklyn Center protest remains peaceful”. Star Tribune. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Kelly, Caroline (April 20, 2021). “Judge in Derek Chauvin trial says Rep. Maxine Waters’ comments may be grounds for appeal”. CNN. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Vallejo, Justin (April 20, 2021). “What would mistrial mean for George Floyd case?”. The Independent. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Pengelly, Martin (April 19, 2021). “Republicans demand action against Maxine Waters after Minneapolis remarks”. The Guardian. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Fordham, Evie (April 18, 2021). “Republicans slam Maxine Waters for telling protesters to ‘get more confrontational’ over Chauvin trial”. Fox News. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Millward, David (April 18, 2021). “Democratic congresswoman urges protesters to stay on streets if Derek Chauvin is cleared”. The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Manu Raju; Veronica Stracqualursi (April 20, 2021). “Democrats block resolution censuring Maxine Waters for Chauvin trial comments”. CNN. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Hupka, Sasha. “Did California Congresswoman Maxine Waters Tamper With The Jury In Derek Chauvin’s Trial?”. www.capradio.org. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Kennedy, Merrit (October 24, 2018). “Apparent ‘Pipe Bombs’ Mailed To Clinton, Obama And CNN”. NPR. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ ““Potentially destructive devices” sent to Clinton, Obama, CNN prompt massive response”. CBS News. October 24, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Weiser, Benjamin; Watkins, Ali (August 5, 2019). “Cesar Sayoc, Who Mailed Pipe Bombs to Trump Critics, Is Sentenced to 20 Years”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ Gonzales, Richard (August 5, 2019). “Florida Man Who Mailed Bombs To Democrats, Media Gets 20 Years In Prison”. NPR.org. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ “Maxine Waters”. Clerk of the United States House of Representatives. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ “Caucus Members”. Congressional Progressive Caucus. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ “Membership”. Congressional Caucus for the Equal Rights Amendment. Archived from the original on September 18, 2024. Retrieved September 20, 2024.

- ^ “About the CEC”. CEC. Retrieved September 11, 2025.

- ^ “Our Mission”. U.S.-China Working Group. Retrieved February 28, 2025.

- ^ “Members”. Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus. Retrieved July 30, 2025.

- ^ “Congressional Record”. NARAL Pro-Choice America.

- ^ “Maxine Waters”. SBA Pro-Life America. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Waters, Maxine (June 24, 2022). “Today, I stand in solidarity with the 36 MILLION women being stripped of their right to decide what is best for themselves. We WILL keep fighting! #BansOffOurBodies”. Twitter. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Montopoli, Brian (August 11, 2011), “Maxine Waters: Why isn’t Obama in black communities?”, CBS News.

- ^ Camia, Catalina (August 18, 2011), “Waters: Black lawmakers hesitant to criticize Obama”, USA Today.

- ^ Allen, Jonathan (August 8, 2011). “Waters to Obama: Iowans or blacks?”. Politico. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ Williams, Joseph (August 29, 2011). “Obama reopens rift with black critics”. Politico. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ Meeks, Kenneth (June 1, 2005), “Back Talk with Maxine Waters” (interview), Black Enterprise.

- ^ Max Greenwood, Maxine Waters: Trump is the most deplorable person I’ve ever met, The Hill (August 4, 2017).

- ^ “Rep. Maxine Waters: Trump advisors with Russia ties are …” MSNBC. February 21, 2017.

- ^ Diaz, Daniella (February 6, 2017). “Waters: Trump ‘leading himself’ to impeachment”. CNN.

- ^ “Maxine Waters Turns Comedian Dick Gregory’s Eulogy into Anti-Trump Speech”. September 20, 2017.

- ^ Lim, Naomi (October 12, 2017), “Maxine Waters: Congress has enough evidence against Trump to ‘be moving on impeachment'”, Washington Examiner.

- ^ Carter, Brandon (August 13, 2017), “Maxine Waters to Trump: Blame for Charlottesville is on your side, not ‘many'”, The Hill.

- ^ Waters, Maxine (August 13, 2017). “Trump has made it clear – w/ Bannon & Gorka in the WH, & the Klan in the streets, it is now the White Supremacists’ House. #Charlottesviille”. @RepMaxineWaters. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ^ Koman, Tess (February 1, 2018). “Maxine Waters Delivers Scathing SOTU Response: ‘Make No Mistake. Trump Is a Dangerous Racist’“. Cosmopolitan. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ^ Ruiz, Joe (March 11, 2018). “Trump again questions Rep. Waters’ intelligence, says she’s ‘very low IQ’“. CNN. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Gajanan, Mahita (April 25, 2018). “Congresswoman Maxine Waters’ Advice for President Trump: ‘Please Resign’“. Time. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Panetta, Grace. “Whip Count: Here’s which members of the House voted for and against impeaching Trump”. Business Insider.

- ^ Folley, Aris (January 13, 2021). “Maxine Waters in impeachment speech says Trump ‘capable of starting a civil war’“. The Hill. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ Wong, Queenie (June 18, 2019). “US lawmaker wants Facebook to halt its Libra cryptocurrency project”. CNET. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ “Stop Very Unscrupulous Loan Transfers from Underprivileged countries to Rich, Exploitive Funds Act (2008 – H.R. 6796)”. GovTrack.

- ^ “Fidel Castro praises congressional delegation to Cuba”. Fox News. March 25, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ “Waters lauds Castro handshake”. Politico. December 10, 2013.

- ^ “In Castro’s Corner”. National Review. July 23, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ “Waters”. The Political Guide. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015.

- ^ a b “In Castro’s Corner”. The National Review. July 24, 2008. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012.

- ^ West Savali, Kirsten (April 26, 2017). “Bigger Than Trump: One-on-One Exclusive With Rep. Maxine Waters”. The Root.

- ^ Muhammad, Jihad Hassan (May 6, 2013). “‘A Song for Assata’ the FBI hunts hip-hop’s hero”. The Dallas Weekly. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- ^ presumably Maxine Waters (September 9, 1998). “Congresswoman Waters issues statement on U.S. Freedom Fighter Assata Shakur”. World History Archives. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ “Aristide says U.S. deposed him in ‘coup d’etat’“. CNN. March 2, 2004. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ “Defying Washington: Haiti’s Aristide Returns to the Caribbean”, Pacifica Radio, March 15, 2004, archived from the original on January 19, 2011, retrieved July 1, 2011

- ^ “Newsmaker profile – Sharon Hay Webster”, Jamaica Gleaner, March 21, 2004, archived from the original on July 17, 2012, retrieved July 1, 2011

- ^ “Aristide leaves Jamaica, heads for South Africa”, CTV News Saskatoon, May 30, 2004, archived from the original on September 29, 2011, retrieved July 1, 2011

- ^ “Senate and House Leaders to Secretary of State Pompeo: Cut Military Aid to Azerbaijan; Sanction Turkey for Ongoing Attacks Against Armenia and Artsakh”. The Armenian Weekly. October 2, 2020.

- ^ Sam Fulwood II, Rep. Waters Labels Bush ‘a Racist,’ Endorses Clinton, Los Angeles Times (July 9, 1992).

- ^ Jenkins, Sally (August 22, 2011). “Maxine Waters to tea party: Go to Hell”. The Washington Post.

- ^ Epstein, Jennifer (August 22, 2011). “Rep. Maxine Waters: Tea party can go to hell”. Politico.

- ^ “Final Vote Results for Roll Call 455, H J RES 114 To Authorize the Use of United States Armed Forces Against Iraq”. Clerk of the United States House of Representatives. October 10, 2002. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ “The Iraq War”. October 22, 2007. Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- ^ “War in Iraq”. November 5, 2007. Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- ^ “Cheney ouster gains backers”. The Washington Times. June 13, 2007. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Murphy, Patricia. “Rep. Maxine Waters: Yank the NFL’s Antitrust Exemption”. Politics Daily. Archived from the original on October 30, 2009. Retrieved October 30, 2009.

- ^ Hall, Carla (February 6, 1994). “Sidney Williams’ Unusual Route to Ambassador Post : Appointments: His nomination has drawn some critics. But his biggest boost may come from his wife, Rep. Maxine Waters”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ How much are they worth? Maxine Waters, Los Angeles Times.

- ^ “Maxine Waters says her sister died from coronavirus”. MSN. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ “Camille Cosby, Kathleen Battle Win Candace Awards”. Jet. Vol. 82, no. 13. Johnson Publishing Company. July 20, 1992. pp. 16–17.

- ^ https://www.washingtonblade.com/2025/11/20/pflag-honors-maxine-waters/

- ^ “1976 CA State Assembly 48”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1978 CA State Assembly 48”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1980 CA State Assembly 48”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1982 CA State Assembly 48”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1984 CA State Assembly 48”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1986 CA State Assembly 48”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1988 CA State Assembly 48”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1990 CA District 29 – D Primary”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1990 CA District 29”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1992 CA District 35 – D Primary”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1992 CA District 35”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1994 CA District 35”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “Statement of Vote November 8, 1994, General Election” (PDF). California Secretary of State. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1996 CA District 35”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “1998 CA District 35”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “2000 CA District 35”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “2002 CA District 35”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ “2004 CA District 35”. ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.